You can trust Advil Liqui-Gels to act fast to relieve your patient’s acute pain1,2

Advil Liqui-Gels act fast to relieve acute pain1

Proven safe and effective, fast acting Advil Liqui-Gels are available in regular, extra strength, and mini formats.1,3,4

Advil Mini-Gels offer fast and effective pain relief in a smaller and easy to swallow format.2,3

Up to 40% of Canadians experience some difficulty swallowing pills.5* The mini size of Advil Mini-Gels makes them easy to swallow. Advil Mini-Gels provide up to 8 hours of pain relief with 2 pills per dose.3

Ibuprofen is the non-steroidal anti-inflammatory ingredient in Advil products.2

* Advil Nielsen BASES Canada.5

Overall & GI Tolerability Profile

Ibuprofen comparative tolerability in a large-scale randomized trial

In the PAIN study, published in Clinical Drug Investigation, overall tolerability of ibuprofen was:2,4

- Statistically equivalent to that of acetaminophen

- Superior to that of ASA

This large scale randomized trial comparing nonprescription doses of ASA, acetaminophen, and ibuprofen in 8,677 adults measured rates of significant adverse events related to tolerability. The primary outcome measure was the number of patients with at least one significant adverse event, defined as an event that was serious, severe or moderate, resulted in a second physician consultation, led to cessation of treatment, or was of missing intensity. Statistical analysis tested for equivalence between ibuprofen and acetaminophen, and for difference with ASA. 2,4*

ASA = acetylsalicylic acid; GI = gastrointestinal.* This was a blinded, multicentre study in general practice of up to 7 days of ASA, acetaminophen (both up to 3 g daily) or ibuprofen (up to 1.2 g daily), administered for common painful conditions, using patient generated data with physician assistance. 1,108 general practitioners included 8,677 adults (2,900 ASA; 2,886 ibuprofen; 2,888 acetaminophen; 3 patients had no code label number). The main indications were musculoskeletal or back pain (48%), sore throat, the common cold and flu (31%).

When used as directed for acute pain, OTC ibuprofen is well tolerated2*

In the PAIN study, which included over 8,500 patients, total GI events (including dyspepsia) and abdominal pain were less frequent with ibuprofen (200 mg) compared to acetylsalicylic acid (500 mg) or acetaminophen (500 mg) (all p<0.035). 2,4

This large scale randomized trial comparing nonprescription doses of ASA, acetaminophen, and ibuprofen in 8,677 adults measured rates of significant adverse events related to tolerability. The primary outcome measure was the number of patients with at least one significant adverse event, defined as an event that was serious, severe or moderate, resulted in a second physician consultation, led to cessation of treatment, or was of missing intensity. Statistical analysis tested for equivalence between ibuprofen and acetaminophen, and for difference with ASA. 2,4*

ASA = acetylsalicylic acid; GI = gastrointestinal; OTC = over the counter.* This was a blinded, multicentre study in general practice of up to 7 days of ASA, acetaminophen (both up to 3 g daily) or ibuprofen (up to 1.2 g daily), administered for common painful conditions, using patient generated data with physician assistance. 1,108 general practitioners included 8,677 adults (2,900 ASA; 2,886 ibuprofen; 2,888 acetaminophen; 3 patients had no code label number). The main indications were musculoskeletal or back pain (48%), sore throat, the common cold and flu (31%).

Cardiovascular safety profile

Cardiovascular risk of ibuprofen is dose-dependent and did not increase with use at OTC doses (≤1200mg/day):6-10

| Ibuprofen dose | Andersohn et al., 2006 | Garcia-Rodriguez,et al., 2008 | van Staa, et al., 2008 | Fosbøl et al., 2009 | McGettigan & Henry., 2011 |

| <1,200 mg/day | RR: 1.05 (95% CI: 0.91, 1.22) | ||||

| ≤1,200 mg/day | RR: 0.99 (95% CI: 0.81, 1.21) | RR: 1.00 (95% CI: 0.80, 1.25) | HR: 0.92 (95% CI: 0.86, 0.97 | RR: 1.05 (95% CI: 0.96, 1.15) |

* Long term continuous use may increase the risk of heart attack or stroke.2

CHD = coronary heart disease; CI = confidence interval; HR = hazard ratio; MI = myocardial infarction; NSAID = nonsteroidal anti-inflammatory drug; OTC = over the counter; RR = relative risk.

† Andersohn F and colleagues conducted a nested case-control study in a cohort of 486,378 persons registered within the United Kingdom General Practice Research Database with at least 1 prescription of an NSAID between June 1, 2000 and October 31, 2004. Rate ratios of acute MI associated with use of COX-2–selective and –nonselective NSAIDs were calculated. The duration of each NSAID prescription was determined by dividing the quantity of prescribed tablets by the number of tablets to be taken daily. “Current” exposure was defined as a NSAID prescription that lasted into the 14-day period before the index date. “Recent” exposure denoted a supply that ended between 15–183 days before the index date, and “past” exposure denoted a supply that ended between 184 days and 1 year before the index date. “Nonuse” was defined as no use of any NSAID during the year before the index date. Rate ratios appeared to increase with higher daily doses of COX-2 inhibitors and were also increased in patients without major cardiovascular risk factors.

Garcia Rodriguez LA and colleagues conducted a population-based, nested case-control analysis of medical records from The Health Improvement Network database in the United Kingdom. The risk of MI was assessed in 716,394 individuals 50–84 years of age between January 2000 and October 2005 (followed up on average of 4.1 years). NSAID exposure was categorized as: “current” when the supply of the most recent prescription lasted until the index date (day of first sign leading to hospitalization) or ended in the 7 days before the index date; “recent”, when it ended 8–90 days before the index date; “past”, when it ended 91–365 days before the index date; and “nonuse”, when there was no recorded use in the year before the index date. “Current use” was subdivided into: “single” when there was use of only one individual NSAID the month before the index date; “multiple” when the patient received prescriptions for 2 or more individual NSAIDs the week before the index date; and “switcher” when there was use of only one NSAID in the week before the index date, but there was use of at least one other NSAID 8–30 days before the index date.

van Staa TP and colleagues conducted a retrospective cohort study that included 729,294 patients from the UK General Practice Research Database (GPRD). The RR of MI was examined in patients that were ≥40 years of age at first NSAID prescription. Data collection started in 1987 and ended for this study in 2006, and the median follow-up for the NSAID cohort was 6.1 years. Patients were followed from the first NSAID prescription (the index date) to the patient’s death, patient’s transfer out of general practice, the last GPRD data collection available for the study (first quarter of 2006), or the date of the first selective COX-2 NSAID prescription, whichever came first. The total follow-up of NSAID users was divided into periods of “current” and “past” exposure, with patients moving between these two groups according to their NSAID use. “Current” exposure was defined as the period from the date of a NSAID prescription to the end of expected duration, plus 3 months. The expected duration of NSAID use was estimated using the daily dose as prescribed by the general practitioner and the number of NSAID tablets.

Fosbøl EL and colleagues conducted a historical cohort study using data from over 1 million healthy Danish individuals over the age of 10 that evaluated the risk of MI and death associated with NSAID use. Healthy is defined according to a history of no hospital admissions and no concomitant selected pharmacotherapy (refer to study for the complete list). NSAIDs were used for 9–34 days.

McGettigan P and Henry D conducted a systematic review of community-based controlled observational studies to determine the cardiovascular risks of NSAIDs. This review included 38 studies with ibuprofen. NSAID prescription was categorized as “current” if it covered a period that included the index day or continued to within 1 week or less of the index day (the day the adverse cardiac event occurred). The outcomes studied included MI, CHD related death or composite of MI, and CHD death.

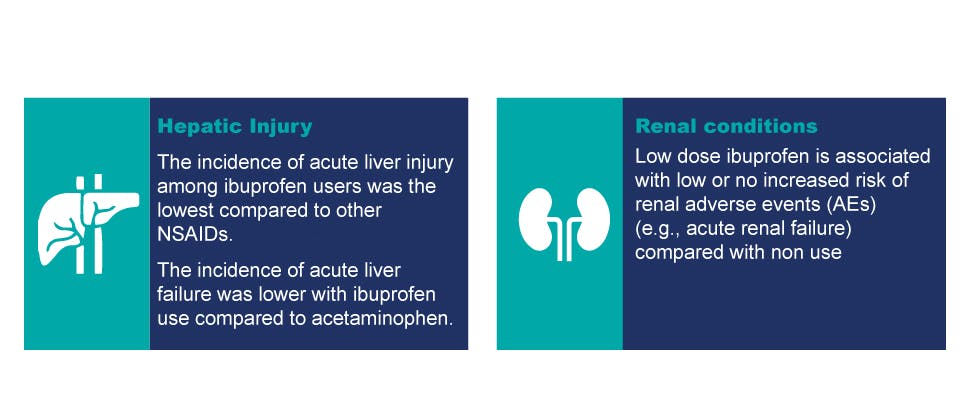

Hepatic and renal safety profile

Clinical studies suggest that ibuprofen was associated with less acute liver injury compared to other NSAIDs:

Archives of Internal Medicine, 1994 (Garcia Rodriguez LA et al.)

- The lowest incidence of liver injury among 8 NSAIDs occurred in ibuprofen users and was 1.6/100000 (1.6/100k). The other incidence in increasing order is as follows: oral diclofenac (3.6/100K), naproxen (3.8/100K), mefenamic acid (2.5/100K), ketoprofen (8.8/100K), piroxicam (6.0/100K), fenbufen (11.9/100K), sulindac (148.1/100K)2,15†

Postgraduate Medicine, 2018 (Moore N et al.)

- Compared to ibuprofen, risks of hepatoxicity are somewhat higher and better documented with acetaminophen, and reported to be higher amongst specific NSAIDs, such as oral diclofenac and sulindac11†

Epidemiologic studies do not suggest that low dose ibuprofen (e.g., ≤1200 mg daily) is associated with an increased risk of renal adverse events (e.g., renal failure, renal injury)12,13‡

American Journal of Epidemiology, 2000 (Griffin MR et al.)

- Use of ibuprofen at ≤1200mg/day led to an odds ratio of 0.94 (95% CI: 0.58, 1.51) for renal AEs (i.e., renal failure)12†

Pharmacotherapy, 1999 (Perez-Gutthann S et al.)

- No major adverse events related to renal injury (i.e., acute renal failure) were identified during the study13†

Pharmacotherapy, 1992 (Furey SA et al.)

- After non-prescription doses of ibuprofen, renal injury (i.e., acute renal failure or any renal injury) were not amongst the reported adverse effects14†

AE = adverse event; CI = confidence interval; GI = gastrointestinal; NSAID = nonsteroidal anti-inflammatory drug; OTC = over the counter.

† Garcia Rodriguez LA and colleagues conducted a retrospective cohort study with secondary case-control analysis. The study included 536 general practitioners' practices in England and Wales for the period October 1987 through August 1991. A total of 625,307 persons who received more than 2 million prescriptions for 1 of 12 NSAIDs, were followed up to estimate the risk of newly diagnosed acute liver injury. The incidence of acute liver injury was 3.7 per 100,000 NSAID users. Sulindac was the only NSAID with a substantially greater risk of acute liver injury than that for the overall NSAID group. The incidence of acute liver injury for indomethacin, diflunisal, tenoxicam, and fenoprofen was not provided. It was concluded that the risk of acute liver injury is sufficiently small as to be of minimal concern for most NSAIDs.

Moore N and colleagues conducted a review of available literature on the GI and hepatic safety of non-aspirin OTC analgesics, including NSAIDs (ibuprofen, ketoprofen, diclofenac, and naproxen) and acetaminophen. Safety in overdose was also reviewed. Articles describing clinical trials, meta-analyses, and epidemiological studies were evaluated for inclusion in the review, and focus was placed on studies discussing doses and durations of use consistent with OTC use. GI effects accounted for 75% of total AEs in the study. Across all studies reviewed here, the risk of serious GI toxicity, including upper GI bleeding and peptic ulcers, was low at OTC doses.

Griffin MR and colleagues is a nested case-control study using Tennessee Medicaid enrollees aged ≥65 years to determine the role of NSAIDs in acute deterioration of renal function. Cases included patients who had been hospitalized with community acquired acute renal failure. For ibuprofen, the odds ratio associated with dosages of ≤1200 mg/day was 0.94 (95% Cl: 0.58, 1.51) and increased as the dosage increased (>1200 to <2400 mg/day was 1.89 [95% Cl: 1.34, 2.67], while >2400 mg/day was 2.32 [95% Cl: 1.45, 3.71]). The researchers identified all prescriptions filled for these drugs in the 365 days before the index date (date of initial hospitalization for cases): 6% current NSAID users began in the past 30 days; 33% had less than 180 days’ use in the past year; 61% had more than 180 days’ use.

Pérez-Gutthann S and colleagues conducted a cohort study in the United Kingdom to evaluate the risk of a newly diagnosed episode of upper GI bleeding, acute liver and renal failure, agranulocytosis, aplastic anemia, severe skin disorders, and anaphylaxis occurring within 30 days after the first prescription for a low dose of oral diclofenac, naproxen, or ibuprofen. There was 22,146 persons using oral diclofenac (≤75 mg), 46,919 using naproxen (≤750 mg), and 54,830 using ibuprofen (≤1200 mg). Age, gender, and comorbidity were similar in the 3 cohorts and consisted of patients aged 15–85 (men and women). Of the 54,830 using ibuprofen (≤1200 mg/day) in the study, there were 2 cases of hepatic injury. A single case of potential renal failure for naproxen was reported and none for ibuprofen.

Furey SA and colleagues evaluated the safety of single doses of non-prescription strength ibuprofen by examining reported side effects from 15 double-blind, randomized, controlled trials conducted of the drug to treat various common painful conditions (e.g., headache, sore throat). All studies included placebo and another nonprescription analgesic, acetaminophen. A total of 878 subjects received ibuprofen 200 mg (n=171) or 400 mg (n=707), 849 subjects received acetaminophen 650 mg (n=237) or 1000 mg (n=612), and 852 subjects received placebo. Subjects were 16–79 years of age, had various pain conditions, but were otherwise in good health. Results indicated that no renal AEs were reported (side effects were predominantly related to the GI tract and the central nervous system).

‡ Safety was demonstrated when ibuprofen was used as directed at a low dose (≤1200 mg/day) and for short term use. Advil should not be taken for fever for more than 3 days or for pain for more than 5 days, unless directed by a physician. Please consult the Product Monograph for complete dosing instructions and safety profile.

Like other NSAIDs, ibuprofen inhibits renal prostaglandin synthesis, which may decrease renal function and cause sodium retention. Renal blood flow and glomerular filtration rate decreased in patients with mild impairment of renal function who took 1200 mg/day of ibuprofen for 1 week. Patients at greatest risk of renal toxicity are those with impaired renal function, heart failure, liver dysfunction, those taking diuretics and the elderly. Use of ibuprofen in patients at risk of renal toxicity or with prerenal conditions should be approached with caution. For full safety information please refer to the warnings and precautions and adverse reactions of the product monograph.

Clinically proven efficacy for mild to moderate acute pain2

There is considerable evidence documenting the efficacy of 200 mg and 400 mg doses of ibuprofen in the treatment of mild to moderate pain in a range of pain models.2

One Advil is often all it takes to relieve mild to moderate pain including: 2

- Sore throat pain

- Headache & migraine

- Muscle aches

- Menstrual pain

- Toothache (dental pain)

Advil also reduces fever.

Clinically proven efficacy in headache pain

Advil (200 mg, 400 mg) has been clinically proven to effectively relieve headache pain.2

Journal of Clinical Pharmacology, 1996 (Schachtel BP et al.)

- A double blind, randomized study comparing ibuprofen 400 mg (N=153) vs. acetaminophen 1000 mg (N=151) and placebo (N=151) found that ibuprofen relieved headache pain significantly better than acetaminophen 1000 mg and placebo. Participants receiving ibuprofen 400 mg reported experiencing no pain significantly faster (at 1, 2, 3, and 4 hours post intake) than those receiving acetaminophen 1000 mg. Approximately, more than 3 times the percentage of subjects receiving ibuprofen 400 mg noted no pain compared to acetaminophen 1000 mg, 3 hours post dose.16*

Headache, 1988 (Schachtel BP et al.)

- A double blind, randomized study compared ibuprofen 400 mg (N=35) to placebo demonstrating a significant analgesic effect on headache within 30 minutes (N=35)17†

* At 30 minutes and 1, 2, 3, and 4 hours post dose, each patient completed the Headache Pain Intensity Scale and the Headache Pain Relief Scale.† Seventy subjects satisfied the admission criteria and included men (21 in treatment group and 15 in placebo) and women (15 in the treatment group and 20 in the placebo group) with a mean age of ~21 years of age. They were instructed to complete a Headache Diary when they experienced a muscle contraction headache. When the headache occurred, they were to swallow a single dose of study medication. Efficacy evaluations were done at 15, 30, 45, 60, 90, and 120 minutes after dosing.

Clinically proven efficacy in migraine pain2,18

Ibuprofen 400 mg has been clinically proven to be effective in relieving the pain of migraine headache and related functional disability.18*

Cochrane Database of Systematic Reviews, 2013 (Rabbie R et al.)

- In a review of 9 studies all participants had a diagnosis of migraines and most had a history of migraine symptoms for at least 12 months before entering the study18

- The proportion of participants experiencing headache relief at 2 hours with ibuprofen 400 mg was 57% vs. 25% with placebo18†

- The proportion of participants with relief from functional disability at 2 hours after ibuprofen 400 mg was 42% vs. 24% with placebo18‡

NNT = number needed to treat.* Included participants all had a diagnosis of migraine headaches according to International Headache Society criteria. The mean age of participants was 30 to 40 years of age in individual studies.† Proportion with ibuprofen is 57% (528/931; range 41% to 72%) and the proportion with placebo was 25% (224/884; range 7% to 50%).‡ The proportion of participants with relief of functional disability at 2 hours after ibuprofen 400 mg was 42% (245/583; range 18% to 76%). The proportion of participants with relief of functional disability at 2 hours after placebo was 24% (129/531; range 13% to 55%).

Common acute pain conditions and the recommended, OTC, evidence-based analgesia19

| Presenting Condition | Evidence-based recommended analgesic |

| Lower back pain | Non-steroidal anti-inflammatory drugs (NSAIDs; e.g., ibuprofen 400 mg 3 times per day) at the lowest possible dose for the shortest possible time. |

| Migraine (medically diagnosed)* | For OTC therapy, NSAID (e.g., ibuprofen) or acetaminophen alone, taking into account comorbidities. |

| Tension-type headache | Aspirin (300 mg three times per day), acetaminophen or NSAID, taking into account patient preference and comorbidities. |

| Sprains and strains | Acetaminophen (500 mg to 1 g four times per day, with a maximum 4 g in 24 hours) or topical NSAID (e.g., ibuprofen or diclofenac gels) are recommended first-line. Consider an oral NSAID (e.g., ibuprofen 400 mg three times per day) 48 hours after the initial injury if needed. |

| Menstrual pain | NSAID (e.g., ibuprofen or naproxen) unless contraindicated. Acetaminophen can be used if a NSAID is contraindicated or provides insufficient pain relief. |

OTC = over the counter.* Migraine must be medically diagnosed before OTC medication can be recommended.

Jane wants fast, effective relief for her migraine pain

Jane* is always on the go. She balances work and family, travel, and friends. She’s active and positive. When a migraine starts to slow her down, she needs fast relief.

Her pain: migraine.

Advil Liqui-Gels act fast to relieve pain including migraine pain and its symptoms.1,2

Ibuprofen 200 mg† and 400 mg have been clinically proven effective in relieving the pain of migraine headache and related functional disability.18

* Fictional case study.† Excluding Advil Mini-Gels.

Recommend Advil to manage your patients’ acute pain

Advil Liqui-Gels

Advil Liqui-Gels act fast to relieve acute pain1Available in regular, extra strength, and mini formats.1,3,4

Advil — for all your patients’ acute pain relief needs

Advil — for all your patients’ acute pain relief needs

Learn more about the Advil product family range.